What is the nation's favourite Roald Dahl book and why his macabre work is truly joyful

Why Roald Dahl is truly the maker of music, the dreamer of (nightmarish) dreams

We live in a world where we try to sanitise everything for our children: bottles, food, cartoons, friendships and fairytales. We're like the Kim and Aggie of childhood. We swish bleach on chubby-wristed creativity and demand wild imaginations come to an equilibrium and sit neatly on structured, self-assembled Swedish shelves.

Say hello to the monster who lives under the bed

I'm not saying we should start feeding wormy spaghetti to our offspring but we should acknowledge the monster who lives under the bed. You see, children are born with an innate knowledge of light and shade. They understand love, encouragement and security because somewhere in their minds, they can see the tendrils of the contrast.

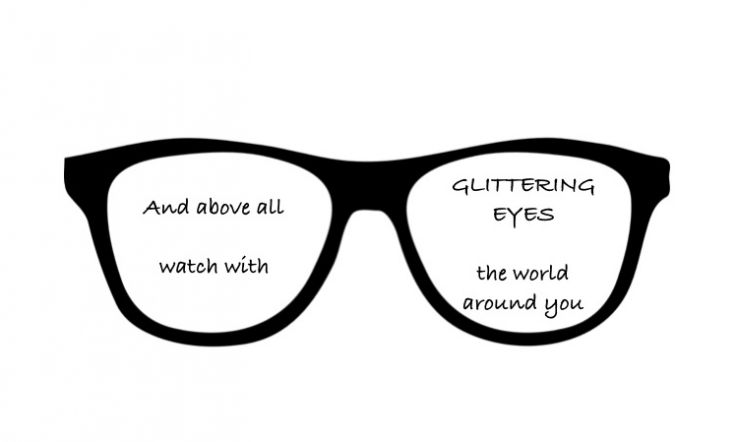

And peeking at the darkness through the keyhole of storytime offers delicious, wide-eyed jitters, the edges of which are softened with wicked humour and a sense of the ridiculous. Which is exactly why Roald Dahl's macabre work is perfect for small people.

The Witches is my favourite work of Dahl's. While Angelica Heuston in the film version is pretty terrifying, nothing can compare with the nightmarish images my own mind created when I read about the vitches of Inkland. I can clearly remember the chill and unease I felt reading about Grandma Helga's childhood friend Erica who went missing and never returned home.

Advertisement

In time, her father noticed her image appear in a farmhouse painting that hung in their home. No one ever saw her move but every morning she would be in a different place, growing older, frozen and staring out at her family. The nightmare fodder of being separated from your parents, of going missing, of being on the outside looking in but never being able to go home; like a baker of childhood terror, Dahl rolled all those layers of fear into one millefeuille of misery.

And then, all of sudden and without warning, Erica disappears, never to be seen again.

And there's the cherry of death plonked on top, Dahl wiping his hands on his floury fearful apron, grinning at his creation.

“It doesn't matter who you are or what you look like, so long as somebody loves you.”

So what moves the pendulum back from something that causes children to scream in terror to something that makes them squeal in delight?

Firstly, it's the dichotomy between the terrible words that tap into childhood fears and the images that invite giggles to bubble up and lighten the moment. Quentin Blake injects a sense of the absurd into the nightmare, pulling it back from the brink of children roaming around the house at 3am, visions of bogeymen dancing in their heads.

Advertisement

Secondly, it's the humour that envelopes the entire narrative. Sure, The Twits is about a passive-aggressive, sniping couple whose marriage is disintegrating into hatred. But wormy spaghetti and convincing your wife that she has a serious illness called 'the shrinks' is comic genius. Matilda is about a child who suffers neglect and emotional abuse at the hands of her parents. Yet she is more than a match for them and punishes them in hilarious ways that are both dark and deserved. The eponymous character in George's Marvellous Medicine is a murderer, short and simple. But his method is like Breaking Bad on crystal meth, antifreeze and horseradish sauce.

Because children are the champions of the world

Finally, there is always a North Star of hope and justice in Dahl's tales. Yes, your parents are vile and your headmistress is the devil who swings you around by your plaits, but there is always a Ms Honey waiting in the wings. Danny may have lost his mother but is held aloft on the shoulders of his father. George's granny was a right wagon. In conclusion, beware those who would cross a child.

Because today is #RoaldDahlDay, I've chosen ten of Dahl's greatest works but I do feel guilty about leaving out Henry Sugar and both the Giraffe and the Pelly. No doubt they will find a way to get even with me involving poison or force-feeding me chocolate cake.

And what if an adult reads one of these books and has nightmares about little mice dying with their grandmothers? Vell then too bad for ze grown-up.

Some elements are not supported yet for this mobile version.